Gabriel G. Tabarani

The Middle East has never been kind to its minorities. Yet few communities embody the precarious balance between survival and erasure more vividly than the Druze of Syria. Scattered across Mount Hermon, the Galilee, Mount Carmel, and above all Jabal al-Druze, this small ethno-religious sect has spent centuries navigating between autonomy and vulnerability. Today, after more than a decade of civil war and the collapse of the Assad regime, the Druze find themselves more exposed than at any time in their modern history. Their story is not simply one of victimhood but of a community caught between the hammer of central authority and the anvil of militant Islamism, searching desperately for a foothold in a Syria that no longer exists.

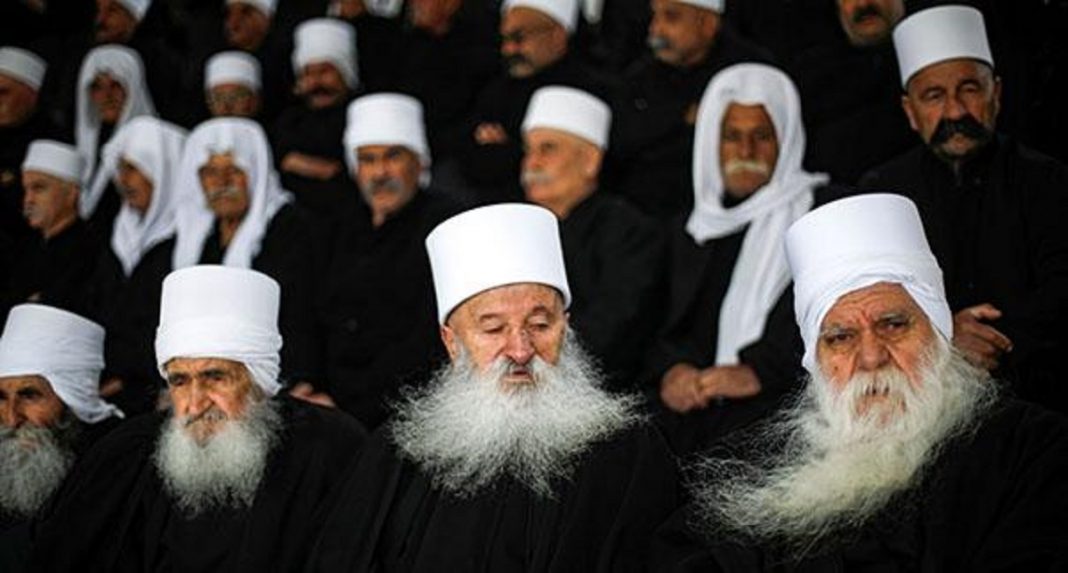

Historically, the Druze survived through a mixture of geographical isolation, clan cohesion, and political pragmatism. They chose the mountains deliberately, using remoteness as a shield from persecution and as a space to cultivate autonomy. Unlike Christians or Shiites, the Druze never built urban centers of their own, preferring to anchor their existence in tight-knit rural societies bound by kinship and faith. Their traditions—endogamous marriage, belief in reincarnation, reverence for their Shaykh-ʻAqls, and a profound sense of brotherhood—created a remarkable internal solidarity. That solidarity enabled them to endure persecution, preserve identity, and play outsized roles in regional politics despite their small numbers.

In Syria, their prominence peaked during the mid-20th century. Sultan Pasha al-Atrash’s leadership of the Great Revolt (1925–1927) cemented the Druze as symbols of Syrian nationalism, while later participation in the Baathist state allowed them temporary access to power. Yet history turned against them in 1966, when a failed coup led by Druze officers triggered a brutal purge. From then on, the Alawites rose and the Druze declined. Still, they adapted: supporting Hafez al-Assad’s secular regime in exchange for economic opportunity and protection against Sunni domination. Pragmatism, once again, was their path to survival.

But the 2011 uprising shattered this fragile arrangement. The Druze were hesitant to join a revolt led by Sunni Islamists who viewed heterodox minorities with suspicion at best and as infidels at worst. Memories of marginalization by the Sunni elite lingered, and the rise of jihadist factions like al-Nusra and the Islamic State turned Druze caution into outright fear. When jihadists massacred Druze in Idlib in 2015 and later in Sweida in 2018, the community’s choice to side with the regime was vindicated in their eyes. Yet loyalty came at a high cost. The regime neglected Druze regions, used kidnappings and sieges as coercion, and even eliminated dissenting leaders like Sheikh Wahid al-Balʻus. Neutrality, or even quiet opposition, proved nearly impossible.

By the time Assad’s state crumbled in late 2024, the Druze were deeply weary and profoundly divided. They greeted the regime’s fall with relief but met the rise of Ahmed al-Sharaa’s jihadist-backed government with alarm. Their skepticism was not paranoia; it was rooted in hard experience. The massacres of Alawites in coastal Syria in early 2025 and the slaughter of Druze civilians in Damascus’s suburbs a few months later confirmed their worst fears. For the Druze, the “new Syria” looked hauntingly like the old Middle East of persecution and exclusion.

Their response has been characteristically pragmatic but fractured. One camp, led by Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajri, has demanded weapons remain in Druze hands and rejected cooperation with a regime dominated by jihadist commanders. Another camp has leaned toward negotiation, seeking to preserve what autonomy they can through compromise. Both camps share one conviction: survival depends on self-defense, not on the goodwill of Damascus. Unlike the Kurds, however, the Druze lack the numbers, territory, and international patronage to pursue full-fledged autonomy. They are left in limbo—too strong to be eliminated outright, too small to impose their own political project.

This limbo is made more precarious by Israel’s shadow. For decades, Israeli strategists have toyed with the idea of a Druze buffer state in southern Syria, a plan rooted more in Israel’s security imagination than in Druze aspirations. While Israeli Druze serve loyally in the IDF and have become integral to Israel’s fabric, their kin across the border remain wary of being branded collaborators. Yet as jihadist militias encircle them and as Damascus seeks to subjugate them through sieges and massacres, Israeli protection becomes both a temptation and a stigma. July 2025 offered a stark example: as regime-backed forces and Bedouin tribes killed more than a thousand Druze in Sweida, Israeli airstrikes intervened to push back government troops. For the first time since the 1970s, Israel openly positioned itself as the Druze’s external shield. But protection can quickly morph into dependency, and dependency into loss of agency.

What the Druze demand is not privilege but security, representation, and dignity. Sheikh al-Hajri’s conditions for normalization with the new regime—local control of Druze security, fair political representation, and a genuine national army—are not radical demands but basic prerequisites for coexistence in a plural Syria. Yet the jihadist nature of the current leadership makes even these modest conditions uncertain. For minorities, the line between inclusion and annihilation has rarely been thinner.

The plight of the Druze should force the international community to confront a grim reality: the collapse of the Syrian state has not liberated its people but has fragmented them into vulnerable enclaves at the mercy of militias. Federalism or decentralization may be the only realistic path forward, yet even those frameworks require leadership willing to accept diversity as a strength rather than a threat. The Druze, like the Kurds, are testing whether such a Syria can ever exist.

If Syria’s future is to be more than a patchwork of fiefdoms under jihadist rule, it must guarantee protections for minorities like the Druze. Otherwise, what remains of one of the region’s most resilient and cohesive communities may be scattered into exile, reduced from a mountain people into another footnote in the region’s long history of forgotten minorities. The tragedy is not only theirs. A Syria without its Druze, Alawites, Christians, or Kurds is not a Syria reborn—it is a Syria diminished, condemned to repeat its cycle of exclusion and bloodshed.

This article was originally published in Arabic on the Asswak Al-Arab website