By Gabriel G. Tabarani

How beautiful and dizzyingly optimistic the early days of Tunisia’s revolution were back in January, and when the dust finally set, the air was tinged pink with the wildest of hopes and expectations. At that time, the Tunisians did not yet know that the brave new dawn that had just risen over their land would illuminate the entire Arab world, from the sands of Egypt to the orchards of Damascus.

It all began in earnest at the trauma ward of the town of Ben Arous where Mohammad Bouazizi was admitted after immolating himself on 17 December 2010, after having received a humiliating slap courtesy of Tunisian policemen. At the time, the university graduate turn subsistence peddler could not have known what the repercussions of his desperate actions would be – producing a butterfly effect resulting in the tornado that would change the political landscape across the Middle East.

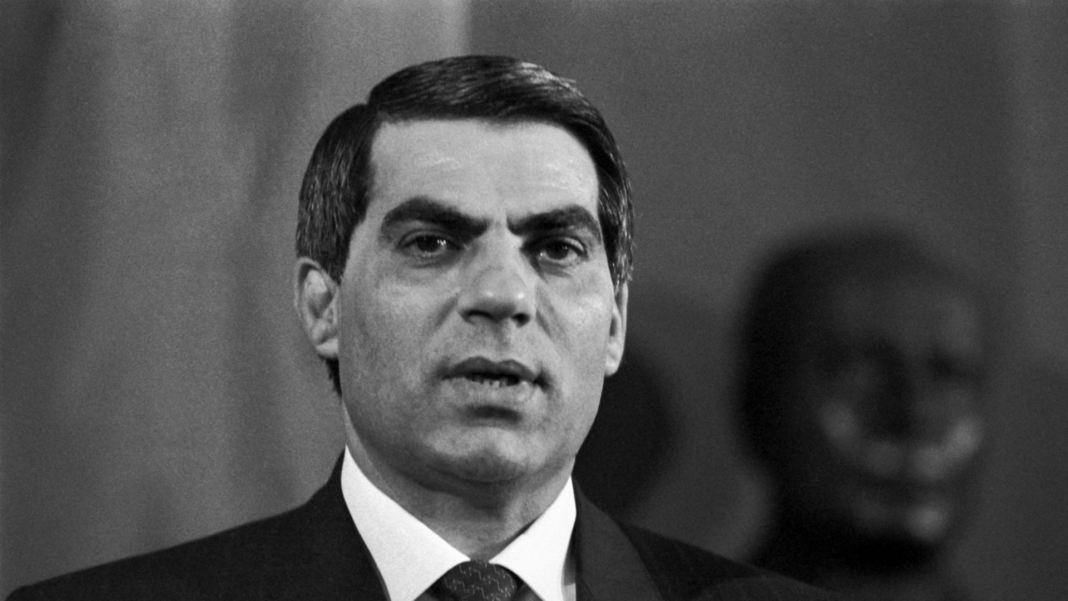

The first, unsuspecting, victim of the ensuring political tumult was Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali the muddled puppet, obeying the orders of a tyrannical wife. In the five months since, the Tunisian outlook is much greyer and harsh realities are beginning to set in as pro-democracy groups are resigned to preaching patience and hoping for better days. Clearly, the revolution is suffering from a hangover -you can hear it and see it.

However, Tunisia has always possessed a fair amount of the elements deemed necessary for establishing and maintaining a political system which at least approaches a Western-style democracy: social cohesion, an educated middle class, a legacy of authentic non-governmental civic and professional organizations, such as trade unions and its bar association as well as a strong tradition of secularism and concern for women’s rights. Furthermore, it benefits from the absence of the grievances and complexes regarding its colonial past and the French language that one finds in neighbouring Algeria.

Nonetheless, Tunisian political life has from the outset been dominated by the office of President, leaving all other political parties and forces emasculated. As such the opening up of Tunisia’s political system carries its own risks which first began to appear after the revolution– in particular the return of the radical “Salafi” movement. In fact, the last serious challenge to the political order prior to the Jasmine Revolution (as January’s uprising is now known) came from the Islamist movement “el-Nahda”. Its leading figure, Rachid Ghannoushi, was once considered an Islamic thinker whose ideas came closer to accepting Western-style democracy and political pluralism than his counterparts elsewhere although one can certainly find other examples of such men. However, now that his party has been officially recognised by the government, the issue is whether “el-Nahda” constitutes an enemy from within for the Jasmine Revolution especially given its soaring popularity?

A video appeared on Facebook on 4 May, in which the former interior minister Farhat Rajhi, a trusted public figure in Tunisia, claimed that Ben Ali loyalists still hold significant sway in the political sphere and that they were planning a military coup, depending on the results of July’s election. Furthermore, he suspected that there is collusion with Algeria to counter the increased popularity of “el-Nahda” (who according to polls could get c.20 percent of votes in the event of an election).

Whether the accusations are true or not does not matter in the paranoia of post-revolution Tunisia. They proved to be a political bombshell as the message was delivered by a highly respected figure whose claims confirmed suspicions already harboured by many.

State practices such as internet censorship and police beatings of journalists, that Tunisians thought had been place firmly in the past, have returned. “First he tried to grab my phone from me and my camera,” said radio journalist Marwa Rekik, accosted by a policeman while covering the protests. “He hit me on the head; I have five stitches in my head.” Her legs were covered in bruises from police batons. Thirteen other journalists also report being beaten by the police.

The government has declined to comment, but in a televised interview on 7 May the Prime Minister Beji Caid Sebsi denied a counter-revolution and called Farhat Rajhi a liar. He said the beating of journalists was a mistake. Rekik finds that hard to believe: “They could say they took me for an ordinary citizen, but there were 14 of us and each of us said we were journalists.” However, that was last May, in the midst of the mess and troubles, when the state seemed overwhelmed by the accumulation of problems, unable to answer the many questions posed by the ordinary Tunisian.

Last Wednesday, the government settled the issue of elections for a Constituent Assembly or parliament. These had been originally scheduled for July 24, however the ballot will take place now on October 23 “in better conditions of freedom and transparency”. However, the wait for legislation necessary to establish a body with the remit to draft a new constitution could last indefinitely – this pause in progress could result in the “habits inherited from the former regime” continuing.

Bloggers, and there are millions, who connected to Facebook and Twitter express their dismay at the current inertia. Extracts quoted by Maghrabia highlight these concerns: “I’m afraid. What the future look like? who will lead the country? a new dictator? The reassuring signals are weak. We are talking about web blocked, torture, trials delay. Time is short.” Highlighted in every such posting, the feeling of apprehension, even fear, is ubiquitous. With good reason, it seems.

The economy, once thriving, is on the road of arduous recovery. Tourism (representing almost 7 per cent of GDP) is falling into the red and nearly a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line, and this is according to official figures – so the truth may be even worse. The young, the driving dynamo of the revolution, fear of unemployment and its inevitable consequence: that of social marginalization.

The Minister of Social Affairs, Mohammad Ennaceur has proposed reform including a new tax system, an increase in wages and improved education and healthcare systems. Once the backbone of Tunisian society, the middle class now barely is making ends meet. Furthermore, the gap between the rich and less rich is far from been filled. In addition, the gross disparity remains between coastal cities and inland, and the unanimous opinion is that the Association Agreement with the EU would need to be expanded to other partners. Tunisia, once the ancient granary of Rome, needs its second-wind at a time when the post-revolution has stalled and it now faces the challenges involved with learning about and establishing an effective democracy.

Certainly, in the life of nations, a mere semester does not count for a lot. At the very least one could augur that it is but the first step on the path to national renewal. However, there remains the risk that in the current vacuum that it could turn out to be a mere prelude to extremism -such an outcome is feared by the majority of Tunisians. An active and vocal minority are working against such a development.

The optimism and euphoria of January’s revolution has given unfortunately way to dread. The revolution is not yet over and its goals are far from assured. Observers still question whether a new social contract can be established between the political and economic elites and the public at large. One which can avoid excessive upheaval and trauma thus placing Tunisia on the path towards a better future?

It seems that the answer must wait at least until next October.

- This commentary was published on thesop.org in USA and in Arabs Today in UK on 10/06/2011